What is it about foie gras that made the city council of Chicago banish the "gourmet" meat from area restaurants this past week? Many angry restaurant owners chose the very day the ban took effect - Aug 22 - to serve foie gras in their establishments for the first time. Slabs of the oily, buttery-tasting goose liver showed up in unconventional dishes such as foie gras pizza - in defiance of the new city ordinance against it. Some restaurant owners said they were just resisting any effort by city government to regulate what they can and can't serve in their restaurants.

In banning the meat considered a delicacy, the city council acted out of concern for animal cruelty. No one seems to dispute that force-feeding geese and ducks up to 4 lbs of grain and fat per day through a tube pushed down their throats is cruel. The birds are force-fed to produce a huge and fat-laced liver, which grows so large that the animals are eventually unable to move or to breathe normally. The livers are prized as a delicacy for their fatty, "buttery" taste.

Animal-rights and vegetarian groups have documented the details of animal misery in the abusive foie-gras industry, such as this article from GoVeg. The geese and ducks are force-fed three times a day. But between the feedings, they're not swimming around a pond or frolicking through the grass on peaceful spacious farms. Like other fowl raised for food, or for eggs, most are confined indoors in cramped quarters between feedings. Many are housed in rows of battery cages that open from the top, similar to the cages that egg-laying hens customarily spend their lives in. We visited and inspected a factory egg farm for a major supermarket chain, and a massive Tyson broiler farm where chickens for meat are raised, as well as a Tyson breeder farm - all of which are described in detail in our book Veggie Revolution. We also interviewed all the farmers, and heard their stories - none of them were entirely thrilled with operating under contract to meatpacking companies whose guiding ethic is shaving pennies from production costs. Environmental issues, animal welfare, consumer health, and workers' rights all take a back seat to shareholder profits for major meatpacking corporations.

Day laborers on factory farms and meatpacking plants, including foie gras farms, are paid very low wages and are often illegal immigrants too vulnerable to object to exploitive and often dangerous working conditions. Usually working under a quota of animals or carcasses processed per minute, they are forced to rush through procedures such as inseminating turkeys, or force-feeding of geese or ducks for foie gras. Consequently, the throats of the geese and ducks are often perforated and scraped as the tube is pushed into place for each feeding. Birds that survive the rough treatment eventually become grossly bloated from their huge and fatty livers, the consequence of overfeeding.

What can you do? If you see foie gras for sale, tell the proprietor of the shop or restaurant that you find the sale distressing, and tell them why. They may not know much about how the liver is produced. Tell them that you won't shop or dine there as long as they carry the product. We interviewed the manager of a Harris Teeter, a large supermarket chain, about the veal they sell in the store, for Veggie Revolution. He said supermarkets are purely customer-driven. They carry what customers buy. Sales of veal have dropped dramatically in recent years due to publicity from animal rights groups, who have educated the public about what veal is exactly - it's beef from calves that are kept isolated in narrow stalls from the age of 1 day to slaughter at 4 months, often chained at the neck to keep their muscles weak and tender. Although Americans are still eating veal, demand in the U.S. has dropped 62% since 1987. I think the same thing will happen with foie gras. It's starting in Chicago; the state of California will follow suit in 2012. As consumers learn more about foie gras, I believe sales will drop.

It's not just food - the sale of SUVs and light trucks has fallen precipitously in recent months due to rising gas prices. Americans are seeking small, fuel-efficient cars that Detroit is unable to deliver. Hence the sales of Asian cars that get good gas mileage - Toyota, Honda, Nissan - have increased. Now Ford and General Motors are scrambling to meet the changing demands of American consumers. Ford is shifting production to flex-fuel cars that can burn a fuel blend that's up to 85% ethanol. They're too late to get in on the hybrid market; Toyota has that one nailed. See our posts of mid June to mid July, especially 7/15/06, for more about that.

Which all just goes to say that power is in consumers' hands. The city council of Chicago started the ball rolling by banning foie gras - now it may be up to consumers to keep that ball rolling. As consumers, we get what we ask for. We vote with our dollars. Most people care about animals, polls show that the vast majority of Americans object to animal abuse. So let's pay attention to what we're eating, and if we're eating animal products, let's get informed and choose products from humanely raised animals. This usually means animals raised on small and local family-owned farms and animals raised at pasture, rather than in confinement. Ask at your local farmers market or natural food store for providers near you. Or check out www.eatwild.com or www.localharvest.org. Foie gras is just the beginning.

For more about the ban in Chicago, see our August 23 post, Fois Gras from Force-fed Geese is Banned in Chicago.

We write about the connections between environment, wildlife, food, and health. Diet choices worldwide are among the top three drivers of global climate change and habitat loss.

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Thursday, August 24, 2006

My Pic of Mountain Goats Looks Like Fleas on a Mountainside

We really wanted to see mountain goats at Mt. Baker in Washington - beautiful shaggy white animals, leaping on impossibly steep and narrow rocky crags, where you're sure they'll fall. You've probably seen them on nature shows, or on posters with dumb captions about hanging on. Somehow they cling to the rocks and vertical surfaces like they had suction cups.

But how do you find a mountain goat? They live only near the timberline in remote mountains. "May be seen at a distance by the adventurer" says our mammal fieldguide. An unlikely find during a 12 day camping trip.

I've learned over the years that the best way to spot wildlife in a new place is to ask other people. I have no pride. If I'm in a national park or a state park, I ask every ranger I see. I ask the people behind the desk at the visitor center, too, if there've been any interesting wildlife sightings in the last couple of days, and where. I ask them every day I'm there. They almost always have an answer. Sometimes they act irritated, but I don't care. Some parks keep a log book of sightings. And if I see a hiker with binoculars or a spotting scope or a handheld radio, I ask them what they've seen and where too.

When we were at Mount Baker in the North Cascade range in Washington state a couple of weeks ago, we ran into a hiker with expensive looking binoculars on the Ptarmigan Ridge trail. We stopped to talk to him. Ken and Alan (husband, son) wanted to ask him about rosy finches and ptarmigans, birds that are common to snowfields and glacier areas around there - birds that we hadn't seen yet. The guy was helpful. Told us where he'd last seen ptarmigans, and said the rosy finches are along the edge of the snow. Yeah, there was still snow there in August.

We never did see the finches or ptarmigans, but we ran into the same guy on a different trail later, and he told us exactly where he'd just seen some mountain goats. So we ran back to the spot. Sure enough, there was a herd of about 20 - mostly mothers and kids. They were on the other side of the valley, not a close-up view by any means, but still good enough to mark down in the field guide as a definitely spotting.

Here's my pathetic picture of the mountain goats - they look like fleas on the mountainside. But we looked at them through the spotting scope and they were definitely mountain goats.

Here's my pathetic picture of the mountain goats - they look like fleas on the mountainside. But we looked at them through the spotting scope and they were definitely mountain goats.

Here's a better picture of a mother mountain goat and her young, taken on Snagtooth Mt in Washington by Alan Bauer:

But how do you find a mountain goat? They live only near the timberline in remote mountains. "May be seen at a distance by the adventurer" says our mammal fieldguide. An unlikely find during a 12 day camping trip.

I've learned over the years that the best way to spot wildlife in a new place is to ask other people. I have no pride. If I'm in a national park or a state park, I ask every ranger I see. I ask the people behind the desk at the visitor center, too, if there've been any interesting wildlife sightings in the last couple of days, and where. I ask them every day I'm there. They almost always have an answer. Sometimes they act irritated, but I don't care. Some parks keep a log book of sightings. And if I see a hiker with binoculars or a spotting scope or a handheld radio, I ask them what they've seen and where too.

When we were at Mount Baker in the North Cascade range in Washington state a couple of weeks ago, we ran into a hiker with expensive looking binoculars on the Ptarmigan Ridge trail. We stopped to talk to him. Ken and Alan (husband, son) wanted to ask him about rosy finches and ptarmigans, birds that are common to snowfields and glacier areas around there - birds that we hadn't seen yet. The guy was helpful. Told us where he'd last seen ptarmigans, and said the rosy finches are along the edge of the snow. Yeah, there was still snow there in August.

We never did see the finches or ptarmigans, but we ran into the same guy on a different trail later, and he told us exactly where he'd just seen some mountain goats. So we ran back to the spot. Sure enough, there was a herd of about 20 - mostly mothers and kids. They were on the other side of the valley, not a close-up view by any means, but still good enough to mark down in the field guide as a definitely spotting.

Here's my pathetic picture of the mountain goats - they look like fleas on the mountainside. But we looked at them through the spotting scope and they were definitely mountain goats.

Here's my pathetic picture of the mountain goats - they look like fleas on the mountainside. But we looked at them through the spotting scope and they were definitely mountain goats.Here's a better picture of a mother mountain goat and her young, taken on Snagtooth Mt in Washington by Alan Bauer:

Here (below) is a mature male mountain goat taken by Ron Niebrugge at Glacier National Park in Montana. Aren't they beautiful?

Mountain goats are always white, have a definite "beard," and have black hooves and short smooth dark horns that curve backward. Their habitat is steep slopes and rocky crags near the snowline, often above the timberline in summer. They feed on high mountain vegetation, grow up to 300 lbs says our field guide to the mammals by Wm Burt. Found in national parks of the NW - Mt. Ranier National Park in Washington and Glacier NP in Montana, Banff and Jasper in Canada. Also Black Hills of S. Dakota. They have been introduced into Olympic National Park and North Cascades NP in Washington.

The only animals they could be confused with in high mountains are bighorn sheep, which have very different massive yellowish spiral-shaped horns. We saw a few bighorn sheep in Yellowstone a few years back and they do look very different because of the horns and usually the color of the coat. Here is a mature bighorn sheep:

Bighorn sheep can be gray, black, brown or white. Like mt goats, they're found on mt slopes, but their range extends all the way from the NW down into northern Mexico. They don't require cold climates. And they're not as elusive as mountain goats.

Bighorn sheep can be gray, black, brown or white. Like mt goats, they're found on mt slopes, but their range extends all the way from the NW down into northern Mexico. They don't require cold climates. And they're not as elusive as mountain goats.

You might see pronghorn antelope and deer in national parks, but not at the same elevations as mountain goats. The antlers of a pronghorn project forward; deer antlers are branched - different from mt goats. Here's a pronghorn, easy to spot if you happen to go to Yellowstone.

Mountain goat populations aren't endangered but are declining. In nature, they're killed by malnutrition, avalanches, rockslides...and falls. They do fall from time to time. Eagles and cougars eat the young.

But their main threat is humans of course. Habitat loss is the biggest factor, due to new roads for mining and logging. And oil drilling. Trophy hunting also takes a big claim on them. Google Images for "mountain goat" and you'll find plenty of photos of hunters grinning over their dead mountain goat. These goats reproduce more slowly than most hooved animals, which makes them less resilient to threats. Estimates of their current population in North America are 40,000 to 100,000. Not too bad but, like I said, declining. What can you do? Let your local legislators know that you care about wildlife. Write them letters and ask them to make habitat conservation a top priority.

For more info about mountain goats, go here.

Mountain goats are always white, have a definite "beard," and have black hooves and short smooth dark horns that curve backward. Their habitat is steep slopes and rocky crags near the snowline, often above the timberline in summer. They feed on high mountain vegetation, grow up to 300 lbs says our field guide to the mammals by Wm Burt. Found in national parks of the NW - Mt. Ranier National Park in Washington and Glacier NP in Montana, Banff and Jasper in Canada. Also Black Hills of S. Dakota. They have been introduced into Olympic National Park and North Cascades NP in Washington.

The only animals they could be confused with in high mountains are bighorn sheep, which have very different massive yellowish spiral-shaped horns. We saw a few bighorn sheep in Yellowstone a few years back and they do look very different because of the horns and usually the color of the coat. Here is a mature bighorn sheep:

Bighorn sheep can be gray, black, brown or white. Like mt goats, they're found on mt slopes, but their range extends all the way from the NW down into northern Mexico. They don't require cold climates. And they're not as elusive as mountain goats.

Bighorn sheep can be gray, black, brown or white. Like mt goats, they're found on mt slopes, but their range extends all the way from the NW down into northern Mexico. They don't require cold climates. And they're not as elusive as mountain goats.You might see pronghorn antelope and deer in national parks, but not at the same elevations as mountain goats. The antlers of a pronghorn project forward; deer antlers are branched - different from mt goats. Here's a pronghorn, easy to spot if you happen to go to Yellowstone.

Mountain goat populations aren't endangered but are declining. In nature, they're killed by malnutrition, avalanches, rockslides...and falls. They do fall from time to time. Eagles and cougars eat the young.

But their main threat is humans of course. Habitat loss is the biggest factor, due to new roads for mining and logging. And oil drilling. Trophy hunting also takes a big claim on them. Google Images for "mountain goat" and you'll find plenty of photos of hunters grinning over their dead mountain goat. These goats reproduce more slowly than most hooved animals, which makes them less resilient to threats. Estimates of their current population in North America are 40,000 to 100,000. Not too bad but, like I said, declining. What can you do? Let your local legislators know that you care about wildlife. Write them letters and ask them to make habitat conservation a top priority.

For more info about mountain goats, go here.

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

Foie Gras from Force-fed Geese is Banned in Chicago

On Tuesday, Chicago became the first city in the nation to outlaw foie gras - the fattened livers of geese and ducks. The city council banned the stuff from restaurants because they consider the method of producing it to be animal cruelty. Foie gras is made by force-feeding geese and ducks through a pipe stuck down their throats.

To make foie gras, the birds - usually geese - are force fed much more than they would normally eat. The feed is usually corn saturated with fat. The extra food and the fat cause their livers to swell to multiples of their normal size, so big that the geese have trouble walking. The liver becomes laced with fat, giving the liver a smooth buttery taste. So they say.

The Chicago Department of Public Health will be in charge of enforcing the ban on foie gras. Restaurants violating it will first be given a warning, then fined $250 to $500 for a second offense.

It'll be interesting to see how well the ban is enforced. But regardless, it sets an important precedent. I don't know of any other examples of a meat product being banned due to animal cruelty. California has a foie gras ban planned that will begin in 2012, and New York is working on a similar law. A bunch of European countries, plus Israel and Argentina, have already banned it. Is it possible other kinds of meat could follow? Veal would be a good candidate. From what I read about foie gras on Wikipedia, I think the production of veal is at least as cruel, if not more so. I mean, once you start down that road, where do you stop? As we discovered while visiting the factory farms we wrote about in Veggie Revolution, all meat from animals raised in confinement on factory farms is the result of suffering and cruelty.

This ban on foie gras could actually be a huge watershed event for farmed animals of the future, and their advocates. Let's hope so.

For more about foie gras, see our August 26 post, Just What Is Foie Gras??

To make foie gras, the birds - usually geese - are force fed much more than they would normally eat. The feed is usually corn saturated with fat. The extra food and the fat cause their livers to swell to multiples of their normal size, so big that the geese have trouble walking. The liver becomes laced with fat, giving the liver a smooth buttery taste. So they say.

The Chicago Department of Public Health will be in charge of enforcing the ban on foie gras. Restaurants violating it will first be given a warning, then fined $250 to $500 for a second offense.

It'll be interesting to see how well the ban is enforced. But regardless, it sets an important precedent. I don't know of any other examples of a meat product being banned due to animal cruelty. California has a foie gras ban planned that will begin in 2012, and New York is working on a similar law. A bunch of European countries, plus Israel and Argentina, have already banned it. Is it possible other kinds of meat could follow? Veal would be a good candidate. From what I read about foie gras on Wikipedia, I think the production of veal is at least as cruel, if not more so. I mean, once you start down that road, where do you stop? As we discovered while visiting the factory farms we wrote about in Veggie Revolution, all meat from animals raised in confinement on factory farms is the result of suffering and cruelty.

This ban on foie gras could actually be a huge watershed event for farmed animals of the future, and their advocates. Let's hope so.

For more about foie gras, see our August 26 post, Just What Is Foie Gras??

Waves of change, rivers of doubt: Global water issues

Water... it's the source of all life. 70 percent of the planet is covered in it, and more than half of your body is made up of it. We use water everyday to refresh, revive, to subsist... yet, water resources are growing increasingly scarce around the world and access to potable water is alarmingly difficult in some regions.

All life on this planet depends on water, a precious resource. Yet, we are struggling to manage water in ways that are efficient, equitable, and environmentally sound. Many parts of the world will face increasingly dire conditions as populations grow, cities expand, and sources of clean, fresh water disappear.

All life on this planet depends on water, a precious resource. Yet, we are struggling to manage water in ways that are efficient, equitable, and environmentally sound. Many parts of the world will face increasingly dire conditions as populations grow, cities expand, and sources of clean, fresh water disappear.

To avert damaging social and environmental outcomes, we need bold policy reforms. Perverse policies are the main cause of the waste and inefficiency that drive freshwater pollution and over-consumption. Reforming these policies requires governments to implement far-reaching institutional change and promote technical innovation.

. . . Turning ideas into action . . .

In this edition, we look at some core water issues affecting people around the world, including privatization, access to clean water, desalination technology, bottled water debates, and non-point source pollution. Listen now...

In this edition, we look at some core water issues affecting people around the world, including privatization, access to clean water, desalination technology, bottled water debates, and non-point source pollution. Listen now...

Featuring:

Kapua Sproat, attorney, Earth Justice; Duke Sevilla, co-founder and treasurer, Hui o Na Wai `Eha; Alan M. Arakawa, Mayor of Maui; Avery Chumbley, president, Wailuku Water Company; Wenonah Hauter, executive director, Food and Water Watch; Geoffrey Segal, director, Privatization and Government Reform/Reason Foundation; Chuck Swartzle, president, Besco Water Treatment, Inc.; William E. Lobenherz, Michigan Soft Drink Association; Dave Dempsey, Clean Water Action Great Lakes; Karl B. Stinson, operations manager, Alameda County Water District; Dr. Peter Gleick, director, The Pacific Institute; Richard Stover, Energy Recovery Inc; Conner Everts, director, California Statewide De-Sal Response Group.

by NRP The National Radio Project

World Resource Institute

Greener Magazine

Production:

Senior Producer/Host/Writer: Tena Rubio

Contributing Producers: Robynn Takayama, Lester Graham, Brian Edwards-Tiekert.

An hour-long version of this program is available on PRX at http://www.prx.org/pieces/13203

For more information:

Earth Justice

223 South King Street, #400

Honolulu, HI 96813-4501

808-599-2436; ksproat@earthjustice.org

www.earthjustice.org

Mayor, County of Maui

200 South High Street

Wailuku, Maui, HI 96793

808-270-7855; Fax: 808-270-8073

www.co.maui.hi.us/mayor/

Wailuku Water Company

255 E Waiko Rd.,

Wailuku HI 96793-9355

808-244-9570; Fax: 808-242-7068

Hui o Na Wai `Eha

c/o John and Rose Marie Duey

575A Iao Valley

Wailuku, HI 96793-3007

808-242-8565; jduey@maui.net

Food and Water Watch

1400 16th Street NW, Suite 225

Washington, DC 20036

202-797-6550; Fax: 202-797-6560

foodandwater@fwwatch.org

www.fwwatch.org

Clean Water Action National Office

4455 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite A300

Washington, DC 20008

202-895-0420

Besco Water Treatment, Inc.

www.bescowater.com/

The Pacific Institute

654 13th Street, Preservation Park

Oakland, CA 94612

510-251-1600;

www.pacinst.org

Energy Recovery Inc.

1908 Doolittle Drive

San Leandro, CA 94577

510-483-7370

www.energy-recovery.com

To avert damaging social and environmental outcomes, we need bold policy reforms. Perverse policies are the main cause of the waste and inefficiency that drive freshwater pollution and over-consumption. Reforming these policies requires governments to implement far-reaching institutional change and promote technical innovation.

. . . Turning ideas into action . . .

- Commentary: World's Water Resources in Swift Decline. With the start of the "Water for Life" International Decade for Action, we must take steps to insure that our precious freshwater resources are preserved.

- Nutrient Runoff Creates Dead Zone. The trading of nutrient credits may hold the answer to ending the annual "Dead Zone" in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

- Watersheds of the World: Managing water for people and nature. WRI played a lead role in producing a comprehensive database of the world’s river basins.

Featuring:

Kapua Sproat, attorney, Earth Justice; Duke Sevilla, co-founder and treasurer, Hui o Na Wai `Eha; Alan M. Arakawa, Mayor of Maui; Avery Chumbley, president, Wailuku Water Company; Wenonah Hauter, executive director, Food and Water Watch; Geoffrey Segal, director, Privatization and Government Reform/Reason Foundation; Chuck Swartzle, president, Besco Water Treatment, Inc.; William E. Lobenherz, Michigan Soft Drink Association; Dave Dempsey, Clean Water Action Great Lakes; Karl B. Stinson, operations manager, Alameda County Water District; Dr. Peter Gleick, director, The Pacific Institute; Richard Stover, Energy Recovery Inc; Conner Everts, director, California Statewide De-Sal Response Group.

by NRP The National Radio Project

World Resource Institute

Greener Magazine

Production:

Senior Producer/Host/Writer: Tena Rubio

Contributing Producers: Robynn Takayama, Lester Graham, Brian Edwards-Tiekert.

An hour-long version of this program is available on PRX at http://www.prx.org/pieces/13203

For more information:

Earth Justice

223 South King Street, #400

Honolulu, HI 96813-4501

808-599-2436; ksproat@earthjustice.org

www.earthjustice.org

Mayor, County of Maui

200 South High Street

Wailuku, Maui, HI 96793

808-270-7855; Fax: 808-270-8073

www.co.maui.hi.us/mayor/

Wailuku Water Company

255 E Waiko Rd.,

Wailuku HI 96793-9355

808-244-9570; Fax: 808-242-7068

Hui o Na Wai `Eha

c/o John and Rose Marie Duey

575A Iao Valley

Wailuku, HI 96793-3007

808-242-8565; jduey@maui.net

Food and Water Watch

1400 16th Street NW, Suite 225

Washington, DC 20036

202-797-6550; Fax: 202-797-6560

foodandwater@fwwatch.org

www.fwwatch.org

Clean Water Action National Office

4455 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite A300

Washington, DC 20008

202-895-0420

Besco Water Treatment, Inc.

www.bescowater.com/

The Pacific Institute

654 13th Street, Preservation Park

Oakland, CA 94612

510-251-1600;

www.pacinst.org

Energy Recovery Inc.

1908 Doolittle Drive

San Leandro, CA 94577

510-483-7370

www.energy-recovery.com

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Best Place in the World to Spot Orcas from Shore

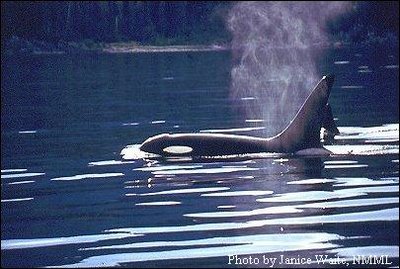

The best place in the world for spotting killer whales (Orcas) from shore is the western coast of San Juan Island, Washington. Or so say the whale fans on the island, and the employees at the Whale Museum. We went there a couple of weeks ago hoping to spot Orcas from shore. Watching from shore has no harmful effects on the whales as whale-watching boats can. Lime Kiln State Park is the island's most popular and maybe most successful spot for watching from shore. June, July, and early August are among the best months.

Lime Kiln State Park is the center of a lot of Orca research. The windows of the park's small lighthouse are filled with graphs and data from doctoral research projects, posted there for whale-viewers to peruse while they wait for whales. A small crowd of 2 to 15 people gathers near the lighthouse every summer afternoon, waiting for the killer whales to come tooling down the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which is 8 miles wide at that point. The Orcas are eating salmon as they travel through. Researchers have identified 3 pods or family groups of Orcas that live in the strait - the J, K, and L pods. The members of a pod stay together most of the time. A pod is matriarchal - all are descendents of a single female who leads the group. J and K pods have 20 something members each; L pod has more than 40. The matriarch of each whale pod is several decades old, and great-grandma to some of the youngest whales.

The afternoon of August 2 we were hanging out at Lime Kiln State Park by the lighthouse, waiting. We were hoping the whales would come soon, we were hungry and tired. The only other people there were a pair of earnest-looking women perched on the rocky outcropping overlooking the water, discussing Orca sightings. One of them had what looked like an electric toothbrush - but it turned out to be a radio, a most useful tool in locating whales. She was listening in to the radio conversation among the whale-watching boats about the Orcas' whereabouts. I asked her what the scoop was, she told me the killer whales were headed our way. Sure enough, after about 5 minutes we could see the small clot of boats that generally follow the whales - three or four small whale-watching boats with clients, and one or two private boats. We could see the boats long before we could see any whales. The first we saw of the whales themselves was just the splashing water as they breached, or leapt from the water and slapped back down on the surface, something they apparently do just for fun.

After a few more minutes, we could see more than splashing - we could see the beautiful black and white bodies of the killer whales, swimming and apparently playing.

Killer whales are the top of the food chain. No animals can kill adult Orcas, not even Great White Sharks. Orcas can kill almost anything they want to kill - other whales and sharks included. Although the resident J, K, and L pods eat mostly salmon, the "transient" Orcas that just move through the San Juan Island area on the way to somewhere else feed heavily on marine mammals. They can toss a seal in the air like popcorn, can snarf down sea lions that weigh a ton, literally. They don't eat humans though. We saw sea kayakers very near the whales - the whales never bother them. Why? Same with wolves. Wolves never attack humans, although they easily could. I don't know why.

We were told that, on some days at Lime Kiln State Park, the whales swim through the water right below the lighthouse, right through the sea kelp along the shore (which is deep right at the shore line). We weren't so lucky though. The whales we saw were much farther out. We could see and hear their spouts (exhaled breaths) though, at times. A spout started with a puffing sound, like air blown suddenly out of pursed lips. The subsequent whoosh had a resonance as of air coming from a deep and hollow chamber. Hard to describe. I guess the whales were 200 yards offshore.

The boats were keeping their distance pretty well - the guideline is at least 100 yards between whale and boat, to minimize disturbance to the whales. The sound of engines is thought to disrupt the whales' communication with each other. (Each pod has its own dialect!) Also, boat exhaust can be a health hazard when the Orcas come up to breathe. Not to mention just the harrassment factor of being trailed every day by a flotilla of boats. But....on the bright side....one of the graphs posted in the lighthouse showed that during the 1970s, an average of 26 boats followed each pod as it moved past Lime Kiln State Park on any given day. Now the average number of boats following a single pod of whales moving down the strait is 8. That's still a lot. But better than 26. The two days I watched though, I didn't see as many as 8 boats around any single group of whales. It was more like 4 or 5. Sometimes only a couple of boats. But maybe that's because the Orca-watching season begins to wane in August. As we watched, the whales stopped moving from time to time, playing and breaching. Then the pod would take off again, moving on down the Juan de Fuca Strait, seeking salmon.

Salmon populations are declining in the area, overfished like everything else. (See www.wildsalmoncenter.org for info on salmon conservation efforts.) But the population of resident Orcas in Juan de Fuca Strait (pods J, K, and L) is holding steady nonetheless at present, numbering in the low 90s. A few decades ago, they were target practice for salmon fishermen. That "sport" has ended.

Most of the time we were watching the whales, all we could see were the fins sticking up. As the Orcas swim, they undulate up and down in an S-shaped path, so that a part of the back rises out of the water at the high points of the undulations. The whales breathe when the back is up, as in the picture below. The visible spout or cloud that results from their breathing is the warm vapor in their breath condensing into droplets in the cooler air. They even swim while they're sleeping - only half the brain sleeps at any given time.

The resident population of Orcas in Juan de Fuca Strait was listed as endangered last year, even though their numbers are steady. They're threatened by water pollution, salmon decline, and boat traffic. In July of 2006, federal officials proposed naming the U.S. half of the strait as critical habitat. You can read more about the critical habitat proposal at Seattlepi.com. To read more about Orca conservation in the San Juan Island area of Washington and Orca biology in general, check out the www.whalemuseum.org. For more about Orca conservation issues in the north Pacific and Alaska area, see the National Marine Mammal Laboratory web site.

Orcas are pretty cool, and very predictable as whales go. I really enjoyed meeting the community of whale fanatics that hang out at Lime Kiln State Park every day, waiting for the whales to show - a group that ranged from kids carrying whale plush toys to research scientists. Wildlife watching used to be a solitary activity for me. But now, I realize that if we as conservationists are to make a difference for wildlife in the future, we have to involve communities of people. We have to develop sustainable ways for people to make a living from the ecosystems around them, such as ecotourism. We especially have to support local people who are trying to transition from "harvesting" of wild animals and plants to more sustainable ways of depending on their environment for their livelihoods. People who depend on the Orcas for their living are more likely to support limits on pollution and boat traffic, more likely to support salmon conservation measures.

If you like whales, if you're interested in seeing a community that is sustainably making a living from local wildlife and ecotourism, visit San Juan Island. And you want to see Orcas from shore, a great place to do it is Lime Kiln State Park.

Sally Kneidel, PhD

Co-author of Veggie Revolution

Orcas; photo from www.estuaries.org

Lime Kiln State Park is the center of a lot of Orca research. The windows of the park's small lighthouse are filled with graphs and data from doctoral research projects, posted there for whale-viewers to peruse while they wait for whales. A small crowd of 2 to 15 people gathers near the lighthouse every summer afternoon, waiting for the killer whales to come tooling down the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which is 8 miles wide at that point. The Orcas are eating salmon as they travel through. Researchers have identified 3 pods or family groups of Orcas that live in the strait - the J, K, and L pods. The members of a pod stay together most of the time. A pod is matriarchal - all are descendents of a single female who leads the group. J and K pods have 20 something members each; L pod has more than 40. The matriarch of each whale pod is several decades old, and great-grandma to some of the youngest whales.

The afternoon of August 2 we were hanging out at Lime Kiln State Park by the lighthouse, waiting. We were hoping the whales would come soon, we were hungry and tired. The only other people there were a pair of earnest-looking women perched on the rocky outcropping overlooking the water, discussing Orca sightings. One of them had what looked like an electric toothbrush - but it turned out to be a radio, a most useful tool in locating whales. She was listening in to the radio conversation among the whale-watching boats about the Orcas' whereabouts. I asked her what the scoop was, she told me the killer whales were headed our way. Sure enough, after about 5 minutes we could see the small clot of boats that generally follow the whales - three or four small whale-watching boats with clients, and one or two private boats. We could see the boats long before we could see any whales. The first we saw of the whales themselves was just the splashing water as they breached, or leapt from the water and slapped back down on the surface, something they apparently do just for fun.

After a few more minutes, we could see more than splashing - we could see the beautiful black and white bodies of the killer whales, swimming and apparently playing.

Killer whales are the top of the food chain. No animals can kill adult Orcas, not even Great White Sharks. Orcas can kill almost anything they want to kill - other whales and sharks included. Although the resident J, K, and L pods eat mostly salmon, the "transient" Orcas that just move through the San Juan Island area on the way to somewhere else feed heavily on marine mammals. They can toss a seal in the air like popcorn, can snarf down sea lions that weigh a ton, literally. They don't eat humans though. We saw sea kayakers very near the whales - the whales never bother them. Why? Same with wolves. Wolves never attack humans, although they easily could. I don't know why.

We were told that, on some days at Lime Kiln State Park, the whales swim through the water right below the lighthouse, right through the sea kelp along the shore (which is deep right at the shore line). We weren't so lucky though. The whales we saw were much farther out. We could see and hear their spouts (exhaled breaths) though, at times. A spout started with a puffing sound, like air blown suddenly out of pursed lips. The subsequent whoosh had a resonance as of air coming from a deep and hollow chamber. Hard to describe. I guess the whales were 200 yards offshore.

The boats were keeping their distance pretty well - the guideline is at least 100 yards between whale and boat, to minimize disturbance to the whales. The sound of engines is thought to disrupt the whales' communication with each other. (Each pod has its own dialect!) Also, boat exhaust can be a health hazard when the Orcas come up to breathe. Not to mention just the harrassment factor of being trailed every day by a flotilla of boats. But....on the bright side....one of the graphs posted in the lighthouse showed that during the 1970s, an average of 26 boats followed each pod as it moved past Lime Kiln State Park on any given day. Now the average number of boats following a single pod of whales moving down the strait is 8. That's still a lot. But better than 26. The two days I watched though, I didn't see as many as 8 boats around any single group of whales. It was more like 4 or 5. Sometimes only a couple of boats. But maybe that's because the Orca-watching season begins to wane in August. As we watched, the whales stopped moving from time to time, playing and breaching. Then the pod would take off again, moving on down the Juan de Fuca Strait, seeking salmon.

Salmon populations are declining in the area, overfished like everything else. (See www.wildsalmoncenter.org for info on salmon conservation efforts.) But the population of resident Orcas in Juan de Fuca Strait (pods J, K, and L) is holding steady nonetheless at present, numbering in the low 90s. A few decades ago, they were target practice for salmon fishermen. That "sport" has ended.

Most of the time we were watching the whales, all we could see were the fins sticking up. As the Orcas swim, they undulate up and down in an S-shaped path, so that a part of the back rises out of the water at the high points of the undulations. The whales breathe when the back is up, as in the picture below. The visible spout or cloud that results from their breathing is the warm vapor in their breath condensing into droplets in the cooler air. They even swim while they're sleeping - only half the brain sleeps at any given time.

The resident population of Orcas in Juan de Fuca Strait was listed as endangered last year, even though their numbers are steady. They're threatened by water pollution, salmon decline, and boat traffic. In July of 2006, federal officials proposed naming the U.S. half of the strait as critical habitat. You can read more about the critical habitat proposal at Seattlepi.com. To read more about Orca conservation in the San Juan Island area of Washington and Orca biology in general, check out the www.whalemuseum.org. For more about Orca conservation issues in the north Pacific and Alaska area, see the National Marine Mammal Laboratory web site.

Orcas are pretty cool, and very predictable as whales go. I really enjoyed meeting the community of whale fanatics that hang out at Lime Kiln State Park every day, waiting for the whales to show - a group that ranged from kids carrying whale plush toys to research scientists. Wildlife watching used to be a solitary activity for me. But now, I realize that if we as conservationists are to make a difference for wildlife in the future, we have to involve communities of people. We have to develop sustainable ways for people to make a living from the ecosystems around them, such as ecotourism. We especially have to support local people who are trying to transition from "harvesting" of wild animals and plants to more sustainable ways of depending on their environment for their livelihoods. People who depend on the Orcas for their living are more likely to support limits on pollution and boat traffic, more likely to support salmon conservation measures.

If you like whales, if you're interested in seeing a community that is sustainably making a living from local wildlife and ecotourism, visit San Juan Island. And you want to see Orcas from shore, a great place to do it is Lime Kiln State Park.

Sally Kneidel, PhD

Co-author of Veggie Revolution

Friday, August 11, 2006

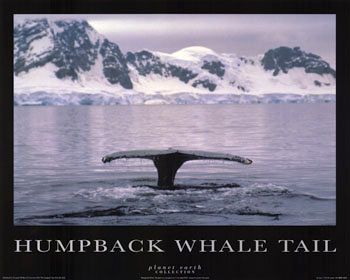

We Saw One Humpback Whale: The Good and Bad on Whale-Watching

fluke of humpback whale; photo courtesy of National Marine Fisheries Service

fluke of humpback whale; photo courtesy of National Marine Fisheries Servicewww.nmfs.noaa.gov/.../

We wanted to see Pacific marine wildlife, and in pursuit of that, we spent the last week of July at a hostel in Tofino, British Columbia - a small village on the wild Pacific coast of Canada's Vancouver Island. Tofino is on the northern edge of Pacific Rim National Park, halfway "up island" as the locals say.

The hostel is called Whalers on the Point Guesthouse (250 725-3443). It overlooks a relatively unpopulated bay where whales sometimes wander. The hostel has a rack of brochures for local whale-watching outfits that take tourists and photographers out to look for whales. The whales most commonly seen in the Tofino area are gray whales, humpbacks, and orcas. Most are migrating through seasonally. But a few are permanent residents. We learned from talking to various locals that two gray whales in particular spend a part of every day lounging in a specific area of sea kelp near one of the many small offshore islands, and have done so for years. Most of the whale-watching companies take their boats to view these two gray whales.

Whale-watching has good and bad aspects. The good is that it brings in around $10 billion in tourist dollars to North American Pacific coastal towns every year. Because a whale-watching outing usually includes viewing other coastal life as well - seals, sea lions, oceanic birds, sea otters, or bears - the income gives local people a strong incentive to preserve marine ecosystems. It gives coastal communities a good reason to leave enough fish to sustain wildlife populations. Ecotourism, which includes whale-watching, can be a sustainable way to "exploit" or make a living from natural resources without diminishing them. But it must have limits. Like all ecotourism, overzealous viewing is a hazard to wildlife populations. With that in mind, many conservation organizations and government bodies have published guidelines to limit and regulate whale-watching. The most widely accepted guideline is to approach no closer than 100 yards, the length of a football field. Another is to linger around a whale no longer than half an hour.

In my experience from staying in three different towns that cater to whale-watchers, these guidelines are generally respected. One boat I saw get too close was turned in by a whale-enthusiast who jotted down the boat's license tag or ID number.

So anyway we chose one of the whale-watching groups in Tofino and went out in their high speed "Zodiac" boat to see the two resident gray whales. A Zodiac is a small pontoon boat that jumps and slams over ocean swells in transit to the whales. The boats are constantly in radio contact with each other, so if there are whales in the area, then the guide for a particular outing already knows exactly where the whales are. But the animals may be miles offshore so the Zodiac can take 45 minutes at full throttle to reach the right area. People with back or neck problems or pregnancies not allowed on the boats, with good reason. It nearly jolted my teeth out. A Zodiac holds about 10 people in addition to the driver. We had to wear orange jump suits that looked like space suits, as protection against the cold and as flotation devices. (That's Sara Kate Kneidel suited up in photo.) British Columbia is cool even in late July - out on the ocean moving fast the air was cold.

So anyway we chose one of the whale-watching groups in Tofino and went out in their high speed "Zodiac" boat to see the two resident gray whales. A Zodiac is a small pontoon boat that jumps and slams over ocean swells in transit to the whales. The boats are constantly in radio contact with each other, so if there are whales in the area, then the guide for a particular outing already knows exactly where the whales are. But the animals may be miles offshore so the Zodiac can take 45 minutes at full throttle to reach the right area. People with back or neck problems or pregnancies not allowed on the boats, with good reason. It nearly jolted my teeth out. A Zodiac holds about 10 people in addition to the driver. We had to wear orange jump suits that looked like space suits, as protection against the cold and as flotation devices. (That's Sara Kate Kneidel suited up in photo.) British Columbia is cool even in late July - out on the ocean moving fast the air was cold.It turned out the day we went that the two resident gray whales had taken the day off and meandered who knows where. We didn't get to see them. But our guide took us to look at a resident humpback whale that had been spotted instead, farther offshore than the boats usually go. The humpbacks have nicks in their tail flukes that make individual identification easy for the people who study them. The one we saw was #117, said our guide.

When we reached the right spot, we could tell because two other small boats were already there, waiting. Our guide cut the engine - the noise can interfere with whale communication underwater. We sat and waited. I'm not sure what I was expecting - that the whale would breach or what. Someone the night before at the hostel had told me that humpbacks are much more playful than grays - breaching and tail-lobbing (slapping the tail on the water) and flipper-slapping and generally making a spectacle.

But the whale didn't do any of that. What the humpback did do what stick its fluke (tail) up out of the water as it dove to feed. The first time all I saw was a quick blur. We waited ten more minutes and the whale did the same thing again. I saw the fluke that time, but barely. The third time the humpback dove, he/she waved the fluke high up in the air and I saw it clearly. #117 had a big chunk missing from one side of its fluke. If you picture a tail or fluke as having two fins or blades on it, one of the blades looked like a big bite had been taken out of it. Our guide said it was likely that an orca (killer whale) which are common in the area in spring had taken a bite when the whale was a baby. I hope he was right. I hope to God it wasn't an injury from a whale-watching boat.

After the third dive, we left - our half hour was up. I don't know for sure if we were annoying the whale or not. I know that it could have left the area easily and we would never have known. In the intervals we waited, we had no way of knowing where the whale was, or if it was still there. As much as I enjoyed seeing it, I felt guilty too. Whether we annoyed it or not, I felt we were trespassing. Anytime I'm close enough to wildlife to get a good look, I'm probably invading its space in some way, even if I'm being respectful.

We saw a bear later near Tofino, foraging in the woods. A park ranger told me that anytime a bear sees a human it's becoming accustomed to humans in a bad way. He said we should yell and be obnoxious to help the bear develop a fear of humans. Bears that get too fearless start foraging in yards and then towns, and such bears eventually wind up being shot as a danger to the community. I saw a newspaper for the nearby town of Ucluelet while we were there, and it featured an article on the front page about two bears being shot by wildlife officers for foraging in garbage cans in town. Ouch.

As our human population grows (the U.S. will soon reach 300 million, if we haven't already), our relationship with wildlife grows more difficult and more complicated.

But anyway back to humpbacks. They're found in both the Atlantic and Pacific, grow to a length of 50 feet. They have long pectoral fins, nearly a third of their body length and a very small dorsal fin well back on the body. They are black except for the white throat, breast, and underside of fluke and flippers. Their flippers have fleshy knobs along the front border, says my "Field Guide to the Mammals" book by Wm Burt, and the fluke is irregular in outline along the posterior border - hence the ease of individual identification. The spout of a humpback is an expanding column of exhaled air and water vapor about 20 ft high, and the baleen (mouthpart for filtering krill or plankton out of seawater) is black. The shape and height of the spout can be important in identifying them, since that's often all the viewer sees. Gray whale spouts are "quick and low", about 10 feet high.

According to the Pacific Biodiversity Institute, the world population of humpbacks is now about 15,000 and is gradually increasing. They are on our federal endangered species list and have been since 1973 when the Endangered Species Act was first passed. Their world population was at one time around 200,000, but declined due to intensive commercial hunting which has since tapered off. The Northern Pacific population is now around 6000. If it reaches 9000, they will be removed from the U.S. endangered species list.

For more information about humpbacks, check out the humpback-whale fact sheet from the American Cetacean Society. And see the PBS web site about humpback whales.

I would love to hear from readers your views about whale-watching and wildlife watching in general. The good, the bad and the ugly.

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Fell Off Cliff While Seeking Seals, Whales, other Marine Mammals

I fell off a cliff last week and broke my arm. Okay, I didn't really fall off a cliff; it was more like sliding down a steep cliff face out-of-control.

The day started serenely enough. We were camping and hiking in Washington State, looking for wildlife - my ecologist husband Ken and our two twenty-something kids, Sara Kate and Alan. On this particular day I was walking along a seaside cliff top on San Juan Island, looking out over the Pacific waters in Puget Sound. I spotted a baby harbor seal on the beach below, parked there by its mom as she went diving for food. I decided to clamber down the cliff to the beach for a better photo angle, while still keeping a respectful distance. (The Northwest Marine Fisheries Service recommends a minimum distance of 100 yards for all marine mammal viewing.) Finding no trail down the cliff, I went anyway, unable to resist the opportunity. I slid on the loose cobble, careened wildly, grabbed a boulder to stop my slide. But I grabbed it a little too vigorously, slammed it actually with my forearm. It hurt, but I didn't do anything about it until yesterday, 5 days after the incident, when we got home to North Carolina. Doctor said forearm is fractured, put a cast on it. C'est la vie ~ a little vacation souvenir. And yes, I discovered, one can hike and camp and manuever for 5 days with an untreated broken arm.

But anyway, back to the cliff and the seal....

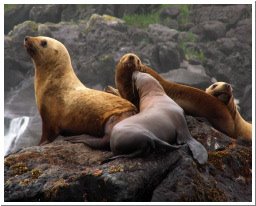

After my collision with the rock, I sat for a moment or two, cursing the cobble and waiting for the exploding stars in my arm to subside. Then I made my way down the remainder of the cliff face to the beach. The beach has lots of rocky outcroppings so it was easy to find a spot where I could photograph the little seal without alarming it. Here's a photo of the little critter napping, taken from a respectable distance.

There are two different families of seals (pinnipeds) that are easy to tell apart. The most common ones in Washington are harbor seals. Harbor seals have rear flippers that point backwards only, and they move on land with an up-and-down undulating motion called "galluphing." They lack external ears - the ear is just an opening on the side of the head. Harbor seals propel themselves in water with their hind flippers. They have thin fur that doesn't trap air, so they rely on blubber for insulation. These features distinguish them from fur seals and sea lions, who have external ears, rear flippers that can face forward and allow them to move fast on land, dense fur that traps air for insulation, and large powerful fore flippers for moving through water.

We saw harbor seals like the baby on the beach at several different spots on the coast of Washington and British Columbia, but saw sea lions only once, off the Pacific coast of Vancouver Island in Canada. I'll write about them in a later post. The male sea lions were huge - they can weigh more 2000 pounds!

After my ill-fated slide down the cliff and a few photos, I checked on the baby harbor seal periodically, from afar, for 2 or 3 hours. But the mom didn't return. So I went to a nearby ranger station for the national park service and told them about the baby - they said they would report it to the "marine mammalogy unit" who would watch it for the next 24 hours to make sure mom came back.

I just now called the park back (San Juan Island National Historical Park) and the fellow who answered the phone, Gordon, told me the beached baby went back out to sea at the next high tide that day, which suggests that mom came back. "They don't go to sea if the mother doesn't come back" said Gordon. I hope Gordon's right. And I hope curious hikers didn't frighten it into the sea before mom came back.

The population of harbor seals on the Pacific coast of the United States seems to be stable from the numbers I've been able to find. According to a 2003 article in the Journal of Wildlife Management, there are about 15,900 harbor seals along the Washington coast and 13,600 around the islands in Puget Sound, and their numbers are holding steady, in spite of challenges. Threats to harbor seals include reduced habitat, increased disturbance, and reduction in populations of fish prey such as hake and herring. I gathered from the journal article that harbor seals also prey on salmon, which generates friction with salmon fishermen. But seals are "protected," according to the federal government's Office of Protected Resources. The office's web site says "All marine mammals are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972."

EXCEPT....and there are a bunch of exceptions. The most insidious exception is "the taking of marine mammals incidental to commercial fishing operations." In other words, it's okay to kill marine mammals if you mean to be catching fish. As we learned while talking to salmon fishermen along Juan de Fuca Strait and Puget Sound and various other waterways of coastal Washington, the "gill nets" set to catch salmon there capture every living thing that comes in contact with the nets, including marine mammals and marine birds such as puffins and auklets. A salmon fisherman we talked with near Cape Flattery on the Olympic Peninsula said his waste "by-catch" from hauling in just one gill net on one day was more than 800 small sharks, all of which drowned, as sharks must keep moving in order to move water across their gills. He tossed all of them back in the water dead, he said.

To voice objections to the use of gill nets, you can check out the action underway by the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. Or google "gill net petition" or "gill net campaign" to find other conservation organizations working to limit the use of gill nets and other dangerous fishing techniques. When activists make a stink, things can and do change.

In the next few posts, I'll write about the other marine mammals we were most fortunate to spot - sea otters, Steller sea lions, and orcas. The August 11 post describes our sighting of a humpback whale, which was a thrill, along with links and conservation information. I'll also post a bit on what we learned about Washington's beautiful old-growth forests and the exploitive timber industry. Activists at work have made a difference. Stay tuned.

The day started serenely enough. We were camping and hiking in Washington State, looking for wildlife - my ecologist husband Ken and our two twenty-something kids, Sara Kate and Alan. On this particular day I was walking along a seaside cliff top on San Juan Island, looking out over the Pacific waters in Puget Sound. I spotted a baby harbor seal on the beach below, parked there by its mom as she went diving for food. I decided to clamber down the cliff to the beach for a better photo angle, while still keeping a respectful distance. (The Northwest Marine Fisheries Service recommends a minimum distance of 100 yards for all marine mammal viewing.) Finding no trail down the cliff, I went anyway, unable to resist the opportunity. I slid on the loose cobble, careened wildly, grabbed a boulder to stop my slide. But I grabbed it a little too vigorously, slammed it actually with my forearm. It hurt, but I didn't do anything about it until yesterday, 5 days after the incident, when we got home to North Carolina. Doctor said forearm is fractured, put a cast on it. C'est la vie ~ a little vacation souvenir. And yes, I discovered, one can hike and camp and manuever for 5 days with an untreated broken arm.

But anyway, back to the cliff and the seal....

After my collision with the rock, I sat for a moment or two, cursing the cobble and waiting for the exploding stars in my arm to subside. Then I made my way down the remainder of the cliff face to the beach. The beach has lots of rocky outcroppings so it was easy to find a spot where I could photograph the little seal without alarming it. Here's a photo of the little critter napping, taken from a respectable distance.

There are two different families of seals (pinnipeds) that are easy to tell apart. The most common ones in Washington are harbor seals. Harbor seals have rear flippers that point backwards only, and they move on land with an up-and-down undulating motion called "galluphing." They lack external ears - the ear is just an opening on the side of the head. Harbor seals propel themselves in water with their hind flippers. They have thin fur that doesn't trap air, so they rely on blubber for insulation. These features distinguish them from fur seals and sea lions, who have external ears, rear flippers that can face forward and allow them to move fast on land, dense fur that traps air for insulation, and large powerful fore flippers for moving through water.

We saw harbor seals like the baby on the beach at several different spots on the coast of Washington and British Columbia, but saw sea lions only once, off the Pacific coast of Vancouver Island in Canada. I'll write about them in a later post. The male sea lions were huge - they can weigh more 2000 pounds!

After my ill-fated slide down the cliff and a few photos, I checked on the baby harbor seal periodically, from afar, for 2 or 3 hours. But the mom didn't return. So I went to a nearby ranger station for the national park service and told them about the baby - they said they would report it to the "marine mammalogy unit" who would watch it for the next 24 hours to make sure mom came back.

I just now called the park back (San Juan Island National Historical Park) and the fellow who answered the phone, Gordon, told me the beached baby went back out to sea at the next high tide that day, which suggests that mom came back. "They don't go to sea if the mother doesn't come back" said Gordon. I hope Gordon's right. And I hope curious hikers didn't frighten it into the sea before mom came back.

The population of harbor seals on the Pacific coast of the United States seems to be stable from the numbers I've been able to find. According to a 2003 article in the Journal of Wildlife Management, there are about 15,900 harbor seals along the Washington coast and 13,600 around the islands in Puget Sound, and their numbers are holding steady, in spite of challenges. Threats to harbor seals include reduced habitat, increased disturbance, and reduction in populations of fish prey such as hake and herring. I gathered from the journal article that harbor seals also prey on salmon, which generates friction with salmon fishermen. But seals are "protected," according to the federal government's Office of Protected Resources. The office's web site says "All marine mammals are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972."

EXCEPT....and there are a bunch of exceptions. The most insidious exception is "the taking of marine mammals incidental to commercial fishing operations." In other words, it's okay to kill marine mammals if you mean to be catching fish. As we learned while talking to salmon fishermen along Juan de Fuca Strait and Puget Sound and various other waterways of coastal Washington, the "gill nets" set to catch salmon there capture every living thing that comes in contact with the nets, including marine mammals and marine birds such as puffins and auklets. A salmon fisherman we talked with near Cape Flattery on the Olympic Peninsula said his waste "by-catch" from hauling in just one gill net on one day was more than 800 small sharks, all of which drowned, as sharks must keep moving in order to move water across their gills. He tossed all of them back in the water dead, he said.

To voice objections to the use of gill nets, you can check out the action underway by the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. Or google "gill net petition" or "gill net campaign" to find other conservation organizations working to limit the use of gill nets and other dangerous fishing techniques. When activists make a stink, things can and do change.

In the next few posts, I'll write about the other marine mammals we were most fortunate to spot - sea otters, Steller sea lions, and orcas. The August 11 post describes our sighting of a humpback whale, which was a thrill, along with links and conservation information. I'll also post a bit on what we learned about Washington's beautiful old-growth forests and the exploitive timber industry. Activists at work have made a difference. Stay tuned.