I fell off a cliff last week and broke my arm. Okay, I didn't really fall off a cliff; it was more like sliding down a steep cliff face out-of-control.

The day started serenely enough. We were camping and hiking in Washington State, looking for wildlife - my ecologist husband Ken and our two twenty-something kids, Sara Kate and Alan. On this particular day I was walking along a seaside cliff top on San Juan Island, looking out over the Pacific waters in Puget Sound. I spotted a baby harbor seal on the beach below, parked there by its mom as she went diving for food. I decided to clamber down the cliff to the beach for a better photo angle, while still keeping a respectful distance. (The Northwest Marine Fisheries Service recommends a minimum distance of 100 yards for all marine mammal viewing.) Finding no trail down the cliff, I went anyway, unable to resist the opportunity. I slid on the loose cobble, careened wildly, grabbed a boulder to stop my slide. But I grabbed it a little too vigorously, slammed it actually with my forearm. It hurt, but I didn't do anything about it until yesterday, 5 days after the incident, when we got home to North Carolina. Doctor said forearm is fractured, put a cast on it. C'est la vie ~ a little vacation souvenir. And yes, I discovered, one can hike and camp and manuever for 5 days with an untreated broken arm.

But anyway, back to the cliff and the seal....

After my collision with the rock, I sat for a moment or two, cursing the cobble and waiting for the exploding stars in my arm to subside. Then I made my way down the remainder of the cliff face to the beach. The beach has lots of rocky outcroppings so it was easy to find a spot where I could photograph the little seal without alarming it. Here's a photo of the little critter napping, taken from a respectable distance.

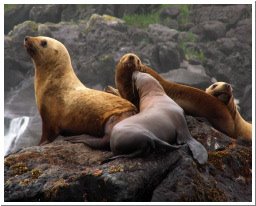

There are two different families of seals (pinnipeds) that are easy to tell apart. The most common ones in Washington are harbor seals. Harbor seals have rear flippers that point backwards only, and they move on land with an up-and-down undulating motion called "galluphing." They lack external ears - the ear is just an opening on the side of the head. Harbor seals propel themselves in water with their hind flippers. They have thin fur that doesn't trap air, so they rely on blubber for insulation. These features distinguish them from fur seals and sea lions, who have external ears, rear flippers that can face forward and allow them to move fast on land, dense fur that traps air for insulation, and large powerful fore flippers for moving through water.

We saw harbor seals like the baby on the beach at several different spots on the coast of Washington and British Columbia, but saw sea lions only once, off the Pacific coast of Vancouver Island in Canada. I'll write about them in a later post. The male sea lions were huge - they can weigh more 2000 pounds!

After my ill-fated slide down the cliff and a few photos, I checked on the baby harbor seal periodically, from afar, for 2 or 3 hours. But the mom didn't return. So I went to a nearby ranger station for the national park service and told them about the baby - they said they would report it to the "marine mammalogy unit" who would watch it for the next 24 hours to make sure mom came back.

I just now called the park back (San Juan Island National Historical Park) and the fellow who answered the phone, Gordon, told me the beached baby went back out to sea at the next high tide that day, which suggests that mom came back. "They don't go to sea if the mother doesn't come back" said Gordon. I hope Gordon's right. And I hope curious hikers didn't frighten it into the sea before mom came back.

The population of harbor seals on the Pacific coast of the United States seems to be stable from the numbers I've been able to find. According to a 2003 article in the Journal of Wildlife Management, there are about 15,900 harbor seals along the Washington coast and 13,600 around the islands in Puget Sound, and their numbers are holding steady, in spite of challenges. Threats to harbor seals include reduced habitat, increased disturbance, and reduction in populations of fish prey such as hake and herring. I gathered from the journal article that harbor seals also prey on salmon, which generates friction with salmon fishermen. But seals are "protected," according to the federal government's Office of Protected Resources. The office's web site says "All marine mammals are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972."

EXCEPT....and there are a bunch of exceptions. The most insidious exception is "the taking of marine mammals incidental to commercial fishing operations." In other words, it's okay to kill marine mammals if you mean to be catching fish. As we learned while talking to salmon fishermen along Juan de Fuca Strait and Puget Sound and various other waterways of coastal Washington, the "gill nets" set to catch salmon there capture every living thing that comes in contact with the nets, including marine mammals and marine birds such as puffins and auklets. A salmon fisherman we talked with near Cape Flattery on the Olympic Peninsula said his waste "by-catch" from hauling in just one gill net on one day was more than 800 small sharks, all of which drowned, as sharks must keep moving in order to move water across their gills. He tossed all of them back in the water dead, he said.

To voice objections to the use of gill nets, you can check out the action underway by the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. Or google "gill net petition" or "gill net campaign" to find other conservation organizations working to limit the use of gill nets and other dangerous fishing techniques. When activists make a stink, things can and do change.

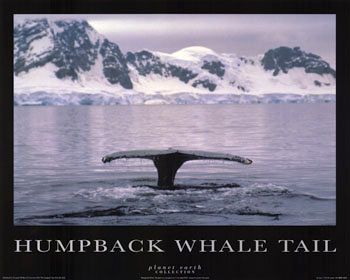

In the next few posts, I'll write about the other marine mammals we were most fortunate to spot - sea otters, Steller sea lions, and orcas. The August 11 post describes our sighting of a humpback whale, which was a thrill, along with links and conservation information. I'll also post a bit on what we learned about Washington's beautiful old-growth forests and the exploitive timber industry. Activists at work have made a difference. Stay tuned.

No comments:

Post a Comment